By Esther Biddle, Old Bedalian

I can remember such anticipation at the opening of the Olivier Theatre at Bedales, not least because we had all seen it rise up slowly over the months and years, but also because we could see how the building would change the scope of dramatic performances and drama lessons in school life.

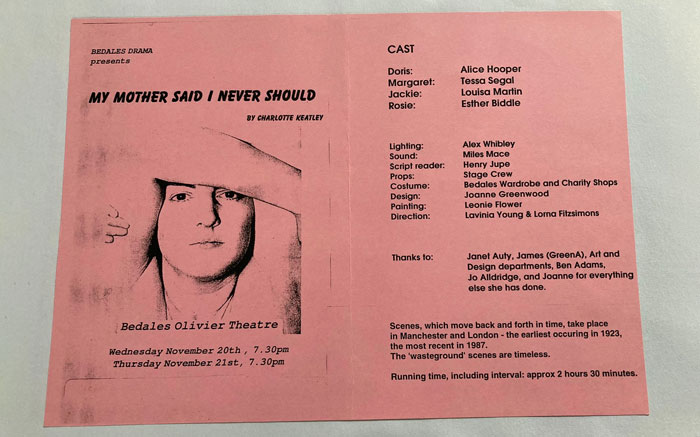

I joined Bedales in Block 3 in 1994 and performing – both as a musician and an actress – was part of the everyday fabric of my time at the school. I was in Block 5 when I was cast in a production of My Mother Said I Never Should, which was directed by two sixth formers and was the first public performance in the newly finished Theatre.

Prior to this, all Drama lessons had been in the Drama Studio, Lupton Hall and the Quad – long before the big glass doors were installed – so the change for all of us was absolutely ginormous! I can remember the thrill of starting rehearsals inside the Theatre and going onto the stage. The auditorium felt so big, and we certainly felt very special and important. Suddenly the work we were producing felt like proper theatre. The beautiful carpentry and framework makes it such a gorgeous building to be in as an audience member, and as young performers we were so excited to have our own proper backstage area with mirrors, lights and a shower!

Everything about that first production was suddenly on such a large scale. Not only the lights and backstage, but the addition of Joanne Greenwood and her amazing sets and costumes took this production – and all those afterwards – to a professional level. In fact, I don’t think anyone can talk about the Theatre without mentioning Joanne. She revolutionised the standard of all the productions at Bedales, which matched the standard of the amazing Theatre itself. I remember high painted pink banners at the back of the stage going all the way up to the top of the doors and being so impressed with the scope of the stage and the theatre space. It gave us as performers a huge playground, and so many entrances and exits through all of the blue doors.

I don’t recall any of us being particularly nervous – most of us were so used to performing at school. Looking back now though, we probably should have been, as it was so well attended because it was the first show in the Theatre and many parents, especially those who had bought seats, wanted to see the new addition to the school.

The play itself looked at four different generations of strong women across the 20th century. As an adult and a mother now, I understand the themes and beats of this play so much more. I hope that we managed to capture some of them in our production.

It was a privilege to appear in this first show at the Olivier Theatre, where I performed many more times throughout my remaining years at Bedales and beyond. Having your Drama lessons in a 350-seat Theatre is an amazing educational environment, and hands down shaped my career as an actress and musician. I feel so lucky to have been at Bedales when it opened.

You must be logged in to post a comment.